By Panagioti Tsolkas

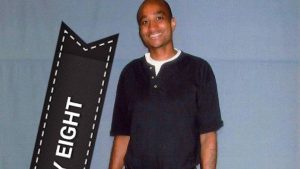

Wayland Coleman, a prisoner at MCI-Norfolk, stepped out of the shower and noticed something strange last year. It was as if his towel was, in his words, “was used to wipe dirt off the floor.” [Image of Coleman to the right]

“I don’t know exactly what is in this water, but I do know that it is in my hair, eyes, nose, and skin,” Coleman wrote in a letter to the Boston Globe. “I ingest it, and with each swallow, I fear for my long-term health.”

He wasn’t alone. In December of 2016, the Norfolk Inmate Council, prisoners tasked with representing the facilities incarcerated population, conducted a survey on health problems facing prisoners there. They presented a report to the administration indicating that almost two-thirds of the prisoners surveyed said they suffered from rashes and other skin problems. Around half noted intestinal issues.

The prisoners’ report also took issue with the sampling results, which were collected from the source rather than the tap, possibly missing major dangers including lead and other sediment from corroded pipes. The water, they said, is not only brown in color but also clogs filters in the communal sinks with sediment.

And yet, despite this inadequate sampling method for testing water quality, the Globe’s review of state records found 43 percent of all samples collected at MCI-Norfolk since 2011 indicated dangerously elevated levels of manganese. This mineral, though considered “naturally occurring” can cause neurological disorders that resemble Parkinson’s disease when consumed in high levels over prolonged periods.

This concerns Coleman who is among the roughly 750 lifers at the prison who experience long-term exposure to the water.

To top it off, prisoners also expressed fury in their report at dogs in the facility, who are trained by prison slave labor to become service providers for non-prisoners with disabilities, were given bottled water. Meanwhile, few prisoners could afford to purchase this water. At 65 cents for 16-once bottles, this equals one-third of the average prisoners daily wage for working at in-house jobs.

“Dogs are provided bottled water, but the human inmates are not,” the report stated. “This creates . . . a strong distrust of the [prison] administrators’ stance on any and all water/health related issues.”

In defense of the prison administration, Peter Lorenz, a spokesman for the state’s Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs said, “More than half the water samples are within compliance.”

Birgit Claus Henn, a Boston University epidemiologist, has spent years studying the impact of manganese. According to her research, the water system should have been repaired if even 10 percent of samples showed elevated levels of the mineral. She says recent studies show manganese can contribute to poor academic performance, diminished verbal function, and other cognitive problems.

“Given that these individuals are chronically exposed, and they aren’t given a choice and can’t seek an alternate source for their water, I would be concerned that this population isn’t adequately protected,” Claus Henn continued.

Marc Nascarella, director of the environmental toxicology program at the state Department of Public Health agreed. “Is it a concern that individuals who are incarcerated don’t have access to clean, fresh water? Yes.”

Despite the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) ordering DOC to install a new water system, DOC has continued making excuses. Christopher Fallon, a spokesman for the Department of Correction, wrote in an e-mail that the new water treatment system was still in the works, but all the bids exceeded the department’s budget for the work leading to a series of contract delays. It was supposed to go online in May 2018. DEP has threatened to fine DOC because of delays.

In February 2017, Coleman was placed in solitary confinement for a month after he mailed the council’s report to the Globe. Soon after, he was stripped of his position on the council.

Senior administrators at MCI-Norfolk declined to answer questions about this incident. But neither the struggle nor the repression ended there.

Over the following year, Coleman worked to establish more support on the outside and developed a plan to circulate water bottles among fellow prisoners. Around the same time, coalition of prisoner rights advocates calling itself Deeper Than Water was forming to assist the effort and raise awareness about the situation.

Christine Mitchell, a Harvard doctoral student in public health and member of Deeper Than Water, said her group saw no other option. “We know [DOC has] the money and the resources to provide clean water, and they haven’t done it.”

Earlier this year Deeper Than Water began raising money to purchase safer bottled water, and opted to let prisoners themselves manage the distribution of the water they helped purchase. Naturally, Coleman stepped up.

But by mid-March 2018 he would be back in solitary confinement for the effort. In response to inquiries about the reason for Coleman’s punishment, Fallon said advocates should have worked with prison officials to provide bottled water. But Mitchell and other members of Deeper Than Water say they couldn’t trust the same prison administrators who had been ignoring the water problem for years to distribute bottled water.

Deeper Than Water members say that they were told Coleman was threatened by a captain that if he continued to purchase cases of water there would be repercussions. The next day on his way to retrieve six more cases, a guard put him in a choke hold, and with the help of a dozen other guards, lugged him to a solitary cell.

Coleman proceeded to go on a food and water strike until he was given filtered or bottled water. Two full-days passed without food or water. On the third day, a guard brought him water from the guards’ bubbler, so he resumed eating. While he was in the solitary unit all of the other prisoners got filtered water as well.

Coleman did end up with three disciplinary reports, but he also succeeded and getting the attention of the new superintendent, as a result of his efforts as well as those of the Deeper Than Water coalition which pushed for call-ins to the facility and co-hosted a solidarity demonstration along with a family member of Coleman’s.

Source: Boston Globe, Democracy Now!, DeeperThanWater.org, WBUR News