“Until these banks find a way to make money on the rehabilitation of people, and not the incarceration,” Greg Cavaluzzi warns, “this will continue.”

Greg Cavaluzzi spent four years in federal prison, eating cold oatmeal and white bread for breakfast and bologna for lunch and dinner. So the first thing he wan ted to do when he was released was to eat “something normal.” When his parents picked him up from Fort Dix in New Jersey, he took them to Wendy’s.

ted to do when he was released was to eat “something normal.” When his parents picked him up from Fort Dix in New Jersey, he took them to Wendy’s.

“We didn’t really talk,” he says. “We ate. We were just so happy to be next to each other.”

He ordered two bacon, egg and cheese sandwiches, and paid for the meal with a JP Morgan Chase debit card featuring a photo of him in his prison-issued khakis, a backdrop measuring his height in the background. The cards are standard in the federal prison system for giving discharged inmates money sent by friends and family or earned at in-prison jobs.

Cavaluzzi’s meal cost about $10. Or as Cavaluzzi puts it: “Everything. It was everything. I was used to making $10 a month.”

He made that money as a librarian in prison, where wages start at 11 cents an hour. But those hard-earned dollars disappeared faster than he expected, and when he called Chase, he found out the reason was fees.

“It just seemed a little…” Cavaluzzi trails off. “It was sketchy.”

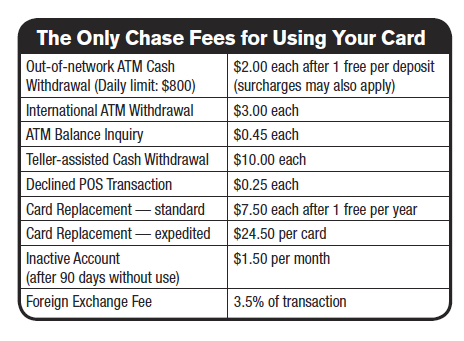

The fees on prison-issued debit cards were agreed to in a 2011 contract with a branch of the Department of the Treasury, which provided the schedule of fees below.

It costs 45 cents to check your balance at an ATM, $1.50 if your account is inactive for 90 days, $2 to withdraw money at a non-Chase ATM, and $7.50 to replace the card a second time within a year.

The absolute numbers aren’t radically high, but experts say even small penalties can be both more significant – and more insidious –for newly released prisoners, who tend to have less money and banking experience, and face many other barriers to reintegrating into society.

“It’s bus fare to a job, it’s a meal, it’s a room for a night,” says Karin Martin, an associate professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. She researches debt and fees in the criminal justice system.

“There’s this split mentality – on the one hand, we are saying we would like to re-integrate people, and on the other hand, we are having lots of policies that undermine their ability to reintegrate,” she says.

Still, contracting with private companies that charge inmates for their services is hardly exceptional.

“The Bureau of Prisons contracts out all kinds of goods and service type things,” says Jack Donson, who was a case manager in the federal prison system for more than two decades. “The institution has food vendors, vending machine vendors, halfway houses.”

In all of these cases, companies have a (literally) captive market, and prisoners frequently complain about being overcharged. Though there is no competition for the business of prison inmates, there is typically competition for the contracts – as there are for most such contracts with the federal government – for sound economic reasons.

“When it comes to products or service that are somewhat standard, easy to describe, where the deliverables are clear and reasonably measurable, then competitive bidding is by far the most efficient method of procurement,” says Steve Tadelis, a UC Berkeley associate professor of business and public policy who has studied government contracts.

A good example of this kind of standardized good or service is a pencil.

“If you’re a government agency and you want to procure pencils, well there are gazillion producers of pencils,” says Tadelis. An open competitive bidding process asks all pencil producers to make an offer and allows that competition to drive down the pencil price.

But a Center for Public Integrity investigation found that the contract with JP Morgan Chase – as well as a contract between the Department of Treasury and the Bank of America for financial services inside of prisons –were not subject to an open, competitive bidding process.

“When I hear ‘no bid contract,’ forget prison environment, that does surprise me a little bit,” Donson says.

From an economist’s view, Tadelis says, it could make sense to skirt competitive bidding, but only if the goods or services are complicated, evolving or difficult to describe.

“From what I’ve read and heard about these issues with the bank accounts and debit cards, I think it’s pretty clear this looks a lot more like a pencil than a fighter jet or a complex IT system,” Tadelis says.

Treasury’s Office of the Inspector General is now investigating the contracts with JP Morgan Chase and the Bank of America and is expected to issue a report later this year.

Gregg Cavaluzzi now works at the Fortune Society, helping to find jobs for other newly released prisoners.

“Until these banks find a way to make money on the rehabilitation of people, and not the incarceration,” he warns, “this will continue.”